ধুমুহাৰ স’তে মোৰ,

বহু যুগৰে নাচোন;

এন্ধাৰো সঁচা মোৰ,

বহু দিনৰে আপোন;

নিজানৰ গান মোৰ,

শেষ হ’ব;

ভাবোঁ তোমাৰ বুকুত।

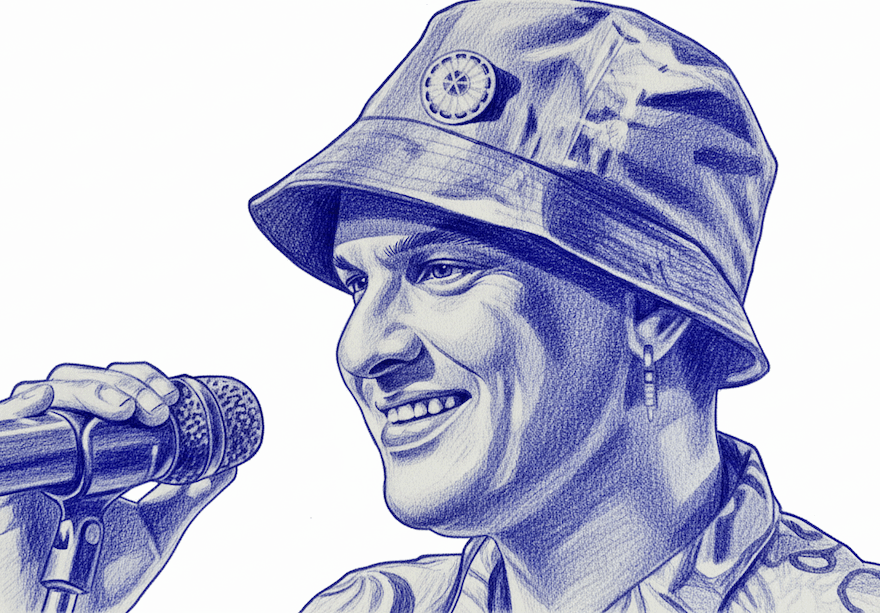

The music world lost more than just a singer on September 19 when Zubeen Garg breathed his last in Singapore at the age of 52. We lost a cultural ambassador, a linguistic bridge-builder, a fearless activist, and most important, a soul who could touch hearts across continents and languages with equal ease. The man born as Zubeen Borthakur on November 18, 1972, in Tura, Meghalaya’s Garo Hills, didn’t just sing – he lived music, breathed melody, and made the world dance to his rhythm for over three decades, all while standing firm for the causes he believed in.

The Lyrical Legacy

Numbers rarely tell the complete story of an artist, but with Zubeen, they certainly help paint the picture of his incredible reach. Over 38,000 songs across 40 different languages and dialects – this isn’t just a discography; it’s a testament to human creativity and linguistic versatility that few artists in world history have ever achieved. From his native Assamese to Hindi, Bengali, English, Sanskrit, Urdu, Tamil, Telugu, Gujarati, and dozens of other regional tongues, Zubeen didn’t just sing in these languages – he embraced their cultural nuances and emotional depths.

His musical journey began in the mid-1990s, and by 1995, he had already started experimenting with Hindi versions of his Assamese compositions through albums like “Chandni Raat”. This early cross-linguistic approach would become his signature style, which made him not just Assam’s voice but India’s multilingual musical ambassador.

But music was never just entertainment for Zubeen. It was his weapon of choice in fighting for justice and equality. A self-described socialist who counted Che Guevara as his idol, Zubeen wore his political ideology not as a badge but as a compass that guided his life’s work. Like the Bolivarian revolutionaries of Latin America who fought for the marginalized and oppressed, Zubeen used his platform to amplify voices that were often silenced.

Man Who Played Life Itself

What made Zubeen truly exceptional wasn’t just his vocal range, but his mastery over 12 different musical instruments. The anandalahari, dhol, dotara, drums, guitar, harmonica, harmonium, mandolin, keyboard, tabla, and various percussion instruments – each became an extension of his creative expression. This multi-instrumental expertise allowed him to compose, arrange, and produce his music with a completeness that few contemporary artists could match.

His approach to music wasn’t mechanical or formulaic. Whether he was strumming a guitar for a romantic ballad or beating the dhol for a traditional Bihu celebration, Zubeen infused each performance with an emotional authenticity that resonated with audiences across demographic and geographic boundaries. This wasn’t just technical skill – it was musical storytelling at its finest.

Silence-Shattering Voice

While music remained his first love, Zubeen’s creative ambitions extended miles beyond recording studios. His foray into acting and film direction, including works like “Mission China”, demonstrated his vision of multimedia storytelling. He wasn’t content being just a playback singer; he wanted to create complete artistic experiences.

But it was in the streets, not the studios, where Zubeen’s true character shone brightest. When the controversial Citizenship Amendment Act threatened the secular fabric of India and particularly stirred anxiety in Assam about demographic changes and indigenous rights, Zubeen didn’t hesitate.

He became one of the most prominent voices against the CAA, performing at rallies and speaking truth to power with the same passion he brought to his music. His opposition wasn’t calculated for publicity – it was rooted in his deep socialist convictions and his commitment to protecting the rights of ordinary people.

His environmental activism proved equally fearless. When the government proposed felling trees to build a new flyover in Guwahati’s “College Street” Dighalipukhuri, Zubeen led protests that captured public imagination and forced authorities to postpone the felling. Here was a man who understood that progress without ecological consciousness was not progress at all – a view that aligned perfectly with his broader socialist worldview of sustainable development for all, not just the privileged few.

His philanthropic work often went unnoticed amid the glamour of his musical career and the controversy of his activism, but those who knew him understood that giving back to society was central to his identity. Educational initiatives, health campaigns, and support for unprivileged communities in Assam – these activities reflected the same passion he brought to his music. He recognized that his platform came with responsibility, and he embraced that responsibility with the same dedication he showed towards his art.

The National Voice

Zubeen’s talent didn’t go unrecognized by the industry. His National Film Award for Best Male Playback Singer in 2009 for the song “Dilruba” from the film “Kismat” was just one of many accolades that acknowledged his contribution to Indian cinema. But beyond formal recognition, he achieved something far more significant – he became the highest-paid singer in Assam, proving that regional artists could command not only national respect but also commercial success.

Songs like “Ya Ali” from “Gangster” introduced him to Hindi film audiences, while tracks like “Bihutoli” rooted him in Assamese folk traditions. This balance between commercial mainstream appeal and cultural authenticity defined his entire career. He never forgot his roots while reaching for the stars.

People’s Zubeen

Zubeen represented something larger than individual musical success – he embodied the cultural pride of northeastern India and the political consciousness of its people. In a country where regional artists often struggle for national recognition, he broke barriers and opened doors. His success proved that language was no barrier to musical excellence, and that authentic regional expression could find universal appreciation.

His fearless honesty and willingness to speak truth to power made him more than an entertainer – he became a voice for social consciousness. Whether challenging hypocrisy in public life, opposing legislation he believed was unjust, protecting the environment, or supporting marginalized communities, Zubeen used his influence to advocate for positive change. This wasn’t just for public relations; it was genuine commitment to using his platform for social good.

His socialist principles weren’t abstract theoretical constructs – they were lived values that informed every aspect of his public life.

In many ways, Zubeen was the musical embodiment of Che Guevara’s revolutionary spirit transplanted to the cultural scenery of India. Where Che fought with guerrilla warfare, Zubeen fought with songs and solidarity. Where Che inspired Latin American revolutionaries, Zubeen inspired a generation of northeastern youth to take pride in their identity while fighting for social justice. Like his idol, he refused to compromise his principles for commercial success or governmental approval.

A Personal Encounter

Music has this incredible power to create unexpected connections, to bring together strangers across time and space in ways that seem almost magical. For me, that magic happened in June 1992, when I was a Class XI student – a fresh school senior who had just entered the new academic year after shedding the load of “Boards” a couple of months ago. I had nothing more than curiosity and youthful enthusiasm driving me forward.

I had travelled to the Kendriya Vidyalaya in Jorhat’s Rowriah to meet a friend whose father, a civilian, had recently been transferred from No. 14 Wing, Indian Air Force Station, Chabua. It was supposed to be a simple visit – catch up with a close friend, maybe explore the new surroundings, and head back home by the evening Jorhat-Tinsukia bus. But sometimes the most ordinary days become the most extraordinary memories.

That afternoon, around 2.30pm, the school had dispersed; while walking across the school grounds, we heard this voice – raw, powerful, yet incredibly melodious – coming from the one of those room, which I don’t remember. (Was it library room or the staff room, or a storeroom, where all the instruments were kept? I really don’t know!) The sound was unlike anything I had heard – a voice that seemed to carry the weight of mountains and the flow of rivers all at once. We followed the music …

There he was – Zubeen Garg, though I wouldn’t learn his name until later that day. He was younger then, maybe 19 or 20, sitting with a guitar, completely absorbed in his music. His hair fell across his forehead as he sang, and his fingers moved across the strings with an ease that spoke of countless hours of practice. But what struck me most was the emotion in his voice – even in that informal setting, every note carried genuine feeling.

We stood there listening for what felt like hours but was probably only 20 minutes. When he finished, he looked up and saw us watching. Instead of being annoyed by the intrusion, he smiled – that warm, genuine smile that would later become familiar to millions of fans. “Did you like it?” he asked simply.

That question, asked with such genuine curiosity and humility, has stayed with me for over three decades. Here was someone with extraordinary talent, yet he cared enough to ask two random teenagers for their opinion.

We talked for another hour so many things, even my classmate’s Gordon Lightfoot album, which he bought along with what was then an “ultramodern” headset. He spoke about wanting to take his music, especially Assamese music to the world, etc, etc. (Who could remember? Not me, certainly.)

Then I forgot about Zubeen and the encounter completely, until I entered university as an inmate in Deepa Complex, Papareddipalya – a nondescript hillside village in the outskirts of Bangalore, with a bunch of Assamese students.

When I learned over two decades later about his incredible journey – the 38,000 songs, the 40 languages, the National Film Award, the fearless activism, the stands he took against powerful interests – I remembered that young man with the guitar and his simple question: “Did you like it?” That encounter taught me that true greatness always begins with genuine humility and authentic curiosity about connecting with others.

The Unending Echo

Zubeen’s passing leaves an enormous void in the musical world and in the conscience of northeastern India. But his voice – that same voice I heard on a summer afternoon in 1992 – continues to echo across languages, cultures, and generations. In those 38,000 songs, millions of us will always find a piece of that young musician who cared enough to ask if we liked what we heard. In his activism and his commitment to socialist principles, we find a reminder that artists have a responsibility to use their platform for the greater good.

He was a Bolivarian rebel in the truest sense – not through armed struggle, but through the power of music and the courage of conviction. He proved that you could be commercially successful without selling your soul, that you could entertain millions while still fighting for justice, and that regional pride and universal solidarity were not contradictory but complementary forces.

Zubeen Garg didn’t just sing for the people – he sang with them, fought alongside them, and never forgot that his gift was meant to serve something larger than himself. That is the legacy that will outlive the silence.

PS: Zubeen’s connection to the school was through his old Jorhat friends, who were “super seniors” – a euphemism for students who never actually passed their Class XII but remained attached to the school to reappear for exams, to represent the school in sports, cultural activities, etc, age limit permitting. My guess is that Zubeen had a few such friends who studied in the school and some juniors still – until that time – linked to the school.

Comments are closed.